Waylon

Jennings

-

Inducted2001

-

Born

June 15, 1937

-

Died

February 13, 2002

-

Birthplace

Littlefield, Texas

Beginnings With Buddy Holly

Waylon Jennings rose from hardscrabble poverty in West Texas to become Buddy Holly’s bassist. Then, he went from Nashville rebel to Outlaw star.

Jennings escaped what he considered the futureless world of Littlefield, Texas, by working in radio in Lubbock, and by picking up the guitar. His big break came when Buddy Holly tapped Jennings to play bass in his new band on a tour through the Midwest in late 1958 and early 1959.

In an oft-told moment, Jennings gave up his seat on an ill-fated flight that would claim the lives of Holly, J. P. Richardson (“the Big Bopper”), and Ritchie Valens. After the crash, Jennings’s musical world crashed around him. Holly had been his mentor, producing his first record (“Jole Blon,” Brunswick, 1958), and Jennings felt responsible, because his last words to Holly had been the joking refrain, “I hope your ole plane crashes” (in response to Holly’s “I hope your damned bus freezes up again”).

From West Texas to Phoenix to Nashville

It took Jennings years to regain some career equilibrium. He first went back to radio in West Texas, then began performing again, ending up at a bar in Phoenix, Arizona, called J. D.’s. Jennings became a local celebrity there, and when Nashville performer Bobby Bare passed through Phoenix and heard Jennings, Bare headed for a pay phone to tell his producer, Chet Atkins at RCA in Nashville, about this raw young talent out in Arizona.

Jennings had already cut some songs in the country-folk vein for then-fledgling A&M Records in Los Angeles, but A&M demurred to Atkins, who signed Jennings to RCA. The singer’s first session for RCA took place on March 16, 1965.

Jennings moved to Nashville and, by sheer chance, became roommates with Johnny Cash; the pair soon cemented their legends as hellraisers. Jennings starred in the 1966 movie Nashville Rebel, scored Top Ten hits with songs such as “The Chokin’ Kind” (#8, 1967) and “Only Daddy That’ll Walk the Line” (#2, 1968), and his 1969 collaboration with the Kimberlys on “MacArthur Park” won a Grammy.

But Jennings chafed under RCA’s tight rein, and at one point he also took a dramatic stand against the status quo: when Chet Atkins turned him over to staff producer Danny Davis, Jennings pulled out a pistol in the studio to protest Davis’s practice of what Jennings felt was studio bullying.

Songs

00:00 / 00:00

00:00 / 00:00

00:00 / 00:00

Becoming an Outlaw

By the early 1970s, Jennings was getting frozen out of country’s mainstream. He retaliated by hiring jazz musician Miles Davis’s maverick manager from New York City, who put him into such high-profile venues as the rock-retro Max’s Kansas City in New York. Gradually, Jennings began to win his war in the studio: he stayed true to his musical instincts and recorded a gallery of landmark recordings, most notably the 1973 albums Lonesome, On’ry and Mean and Honky Tonk Heroes. He also staged an alternative show at the 1973 Disc Jockey Convention in Nashville, with Willie Nelson, Troy Seals, and Sammi Smith joining him in an Outlaw program.

Jennings was dubbed an Outlaw in Nashville for demanding, and eventually getting, what rock groups had been used to having for years—namely, the right to record the material he wanted, in the studio he wanted, and with the musicians he wanted to use. (His friend Nelson won his own independence by moving back to Texas and recording there.) It was, as Jennings later said, a simple matter of artistic freedom.

Jennings was named the Country Music Association’s Male Vocalist of the Year in 1975, but what finally won the battle for Jennings and the Outlaws was the ultimate weapon in corporate wars: sales. Wanted! The Outlaws, an RCA package of songs by Jennings, Nelson, Jennings’s wife Jessi Colter, and Tompall Glaser, was released in January 1976, with only Jennings’s name credited on the album spine (since he was the only one of the four artists still under contract to RCA). The album flew out of record stores and soon became the first album in country music history to be certified platinum, signifying sales of one million copies. The Jennings-Nelson duet “Good Hearted Woman” became a major crossover hit in 1976, as did Jennings’s “Luckenbach, Texas (Back to the Basics of Love)” the following year. Wanted! The Outlaws won the CMA’s Album of the Year award, “Good Hearted Woman” was named CMA Single of the Year, and Jennings and Nelson earned the CMA Duo of the Year honor.

Jennings and Nelson also won a Best Country Vocal Performance by a Duo or Group Grammy for their 1978 hit “Mamas Don’t Let Your Babies Grow Up to Be Cowboys.” Forever linked as “Waylon and Willie,” they began selling records in numbers previously associated with rock album sales, and the Nashville system gradually moved away from a producer-dominated order to one in which the artist shares power.

Videos

“Good Hearted Woman”

Grand Ole Opry, 1978

“I’m a Ramblin’ Man”

Austin City Limits, 1989

Waylon Jennings was dubbed an Outlaw in Nashville for demanding, and eventually getting, what rock groups had been used to having for years—namely, the right to record the material he wanted, in the studio he wanted, and with the musicians he wanted to use.

Photos

-

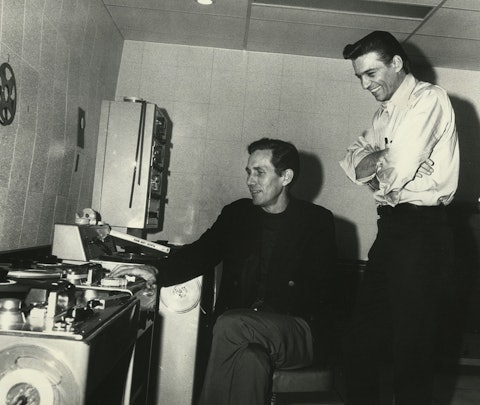

Waylon Jennings and Chet Atkins at a recording session, 1965.

-

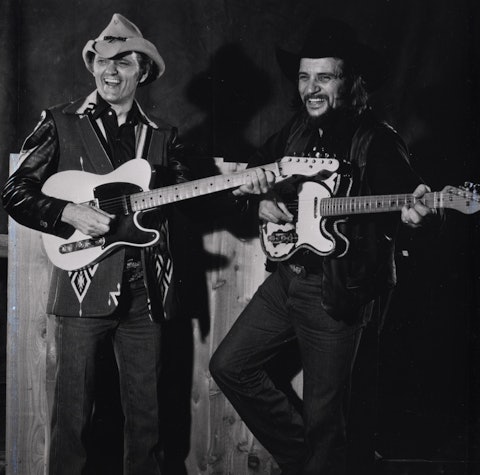

Waylon Jennings and Willie Nelson onstage, 1990. Photo by Vernell Hackett.

-

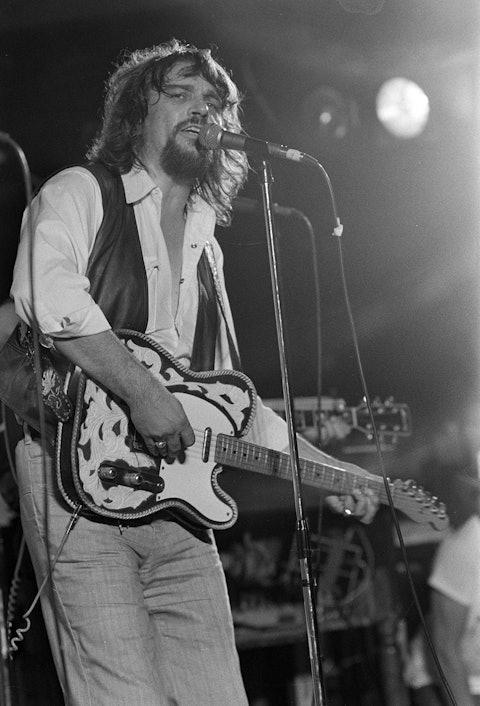

Waylon Jennings onstage, 1974. Photo by Raeanne Rubenstein.

-

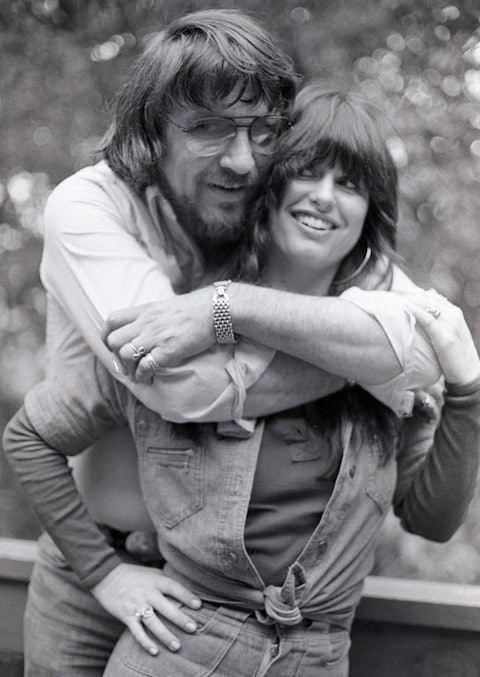

Waylon Jennings and Jessi Colter, 1976. Photo by Raeanne Rubenstein.

-

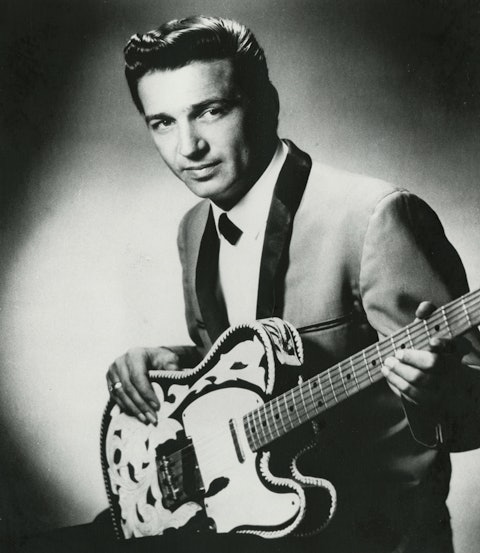

Waylon Jennings, 1960s.

-

Waylon Jennings and Jerry Reed, 1983. Photo by Walden S. Fabry Studios.

-

Waylon Jennings and Johnny Cash onstage.

-

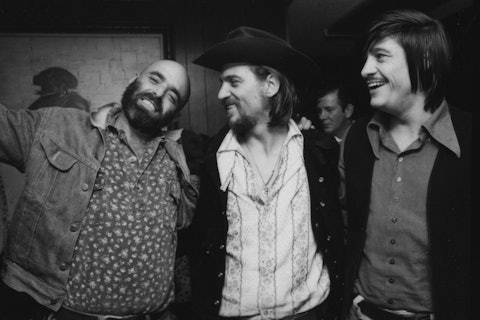

From left: Shel Silverstein, Waylon Jennings, and Vince Matthews, 1972.

-

Waylon Jennings and Jerry Bradley hold a gold record award—signifying sales of half a million copies—for Jennings’s 1978 album I’ve Always Been Crazy, 1979.

-

Waylon Jennings and Sesame Street character Big Bird on the set of the movie Follow That Bird, 1985. Photo by Walden S. Fabry Studios.

From Addict to Redemption

Sadly, for the short term at least, Jennings’s excesses also paralleled those of the rock world, and he was soon spending $1,500 a day on a cocaine habit that eroded his career. He eventually faced his addiction, beat it, and returned to a scaled-down career, with stints on MCA and Epic through the late 1980s and early 1990s.

Jennings was also something of a role model by going back to earn his GED, or high school equivalency diploma. He had dropped out of school in the tenth grade and felt he owed it to his young son to prove his resolution about the importance of education by finishing high school himself.

Jennings stopped touring in 1997 but formed the group the Old Dogs with Bobby Bare, Jerry Reed, and Mel Tillis the next year. They recorded an eponymous double album of songs written by Shel Silverstein. In 1999, Jennings organized the larger Waymore Blues Band, with which he made select appearances into 2001.

Jennings died of complications related to diabetes in February 2002, only a few months after his 2001 election to the Country Music Hall of Fame.

—Chet Flippo

Adapted from the Country Music Hall of Fame® and Museum’s Encyclopedia of Country Music, published by Oxford University Press