Hall of Fame Rotunda

The members of the Country Music Hall of Fame are country music’s elite, and they are appropriately honored in a special place in the museum. The Rotunda is the museum’s most hallowed space and the final stop on the visitor’s museum tour.

A soaring, majestic space commanding respect and reverence, the Rotunda is large, open, and skylit. It was designed to recognize Country Music Hall of Fame members in a style befitting the high honor of membership. The likenesses of all of the Hall of Fame members ring the walls of the Rotunda on bronze plaques, suspended on a metal framework in a loose arrangement symbolizing notes on a musical staff.

The room is round to ensure that every Hall of Fame member has a place of equal importance. The members’ plaques are placed randomly on the walls of the room—except for the newest members of the Hall of Fame, whose plaques can be found on either side of Thomas Hart Benton’s mural The Sources of Country Music.

The Sources of Country Music was that American master painter’s last work, and it is permanently displayed in the Rotunda. Depicting the musical and cultural traditions that shaped country music and America, it is exhibited alongside the bronze images of the men and women who took those sources and created an original and enduring art form.

Architecture of the Rotunda

The 5,300-square-foot space stands seventy feet tall from its floor of southern yellow pine to its circle of clerestory windows above admitting natural light. The title of the famous Carter Family song “Will the Circle Be Unbroken” encircles the room from above, emphasizing the ongoing connectedness of country music’s pioneers to its present.

The melody of “Will the Circle Be Unbroken” is represented on the Rotunda’s exterior in the vertical stone bars arranged like notes on a musical staff. Viewed from the outside, the cylindrical shape of the Rotunda recalls railroad water towers and grain silos found in rural settings. Four disc-shaped tiers on the Rotunda’s roof represent four key formats of recording playback: the 78, the vinyl LP, the 45, and the compact disc.

The tower rising from the Rotunda resembles the iconic, diamond-shaped WSM radio tower, built in 1932 and still in operation. In addition to standing above the Rotunda’s exterior, the tower’s lower half dramatically pierces the interior space, accurately reflecting the entire shape of the actual radio tower. WSM and its Grand Ole Opry were instrumental in the growth of country music. In a broader sense, the Rotunda’s tower symbolizes the importance of all radio and television broadcasting to country music’s growth. The tower also evokes a church steeple, recalling the role of religious culture in country music’s history.

The Plaques

Country Music Hall of Fame honor was created in 1961, and its first three bronze plaques were unveiled in November of that year, honoring Jimmie Rodgers, Fred Rose, and Hank Williams. The Country Music Hall of Fame and Museum’s first building—to house the plaques and to interpret and preserve country music’s history—opened on Music Row in April 1967. Prior to 1967, the plaques were displayed at the Tennessee State Museum in downtown Nashville. In 2001, when the new Country Music Hall of Fame and Museum opened, the plaques were given a special place of honor in the Rotunda.

The plaques are commissioned by the Country Music Association (CMA), which conducts the annual election for new member of the Country Music Hall of Fame. The museum exhibits the plaques through a licensing agreement with the CMA. The plaques aren’t positioned in any particular order. This random arrangement underscores the point that there is no most honored place in the Hall of Fame Rotunda. Election to the Hall of Fame is country music’s highest honor, and once a person is elected to that esteemed group, he or she is the equal of any other member.

THE FINAL PAINTING FROM AN AMERICAN MASTER

The Sources of Country Music

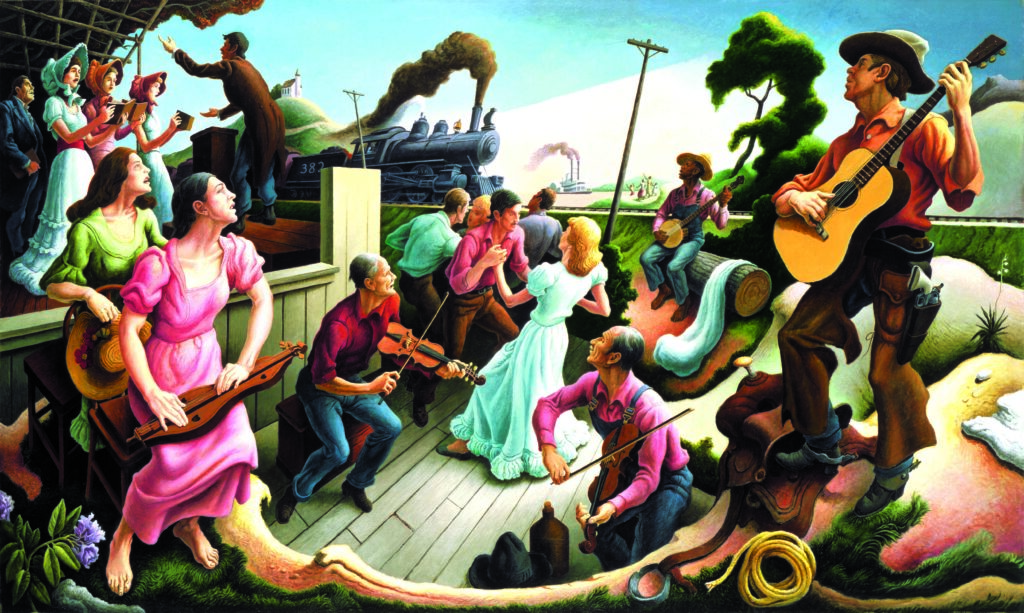

Across the room from the Rotunda entrance is a large, colorful painting depicting musical and cultural contributors to the country music tradition. Viewed from left to right, one sees a gospel choir, a mountain dulcimer player, fiddlers accompanying dancers, a Black banjoist with a cotton sack, and a lone, guitar-playing, singing cowboy, all of whom represent the roots of the music. In the background of the painting is a steamboat on a river, a train with smoke billowing, and a remote country church, which reflect common themes and rural imagery that have permeated country songs.

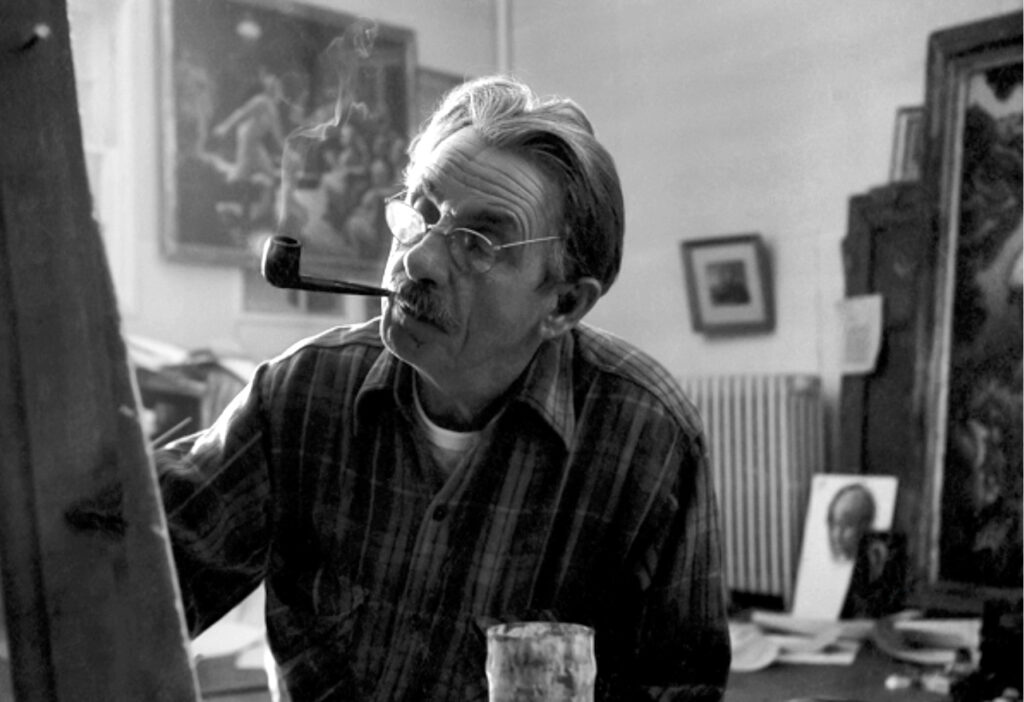

The painting, Thomas Hart Benton’s The Sources of Country Music, was commissioned by the board of the Country Music Foundation in 1973, with financial support from the National Endowment for the Arts and the Tennessee Arts Commission. A celebrated American Regionalist painter, Benton had by that time created many works that could be found in the collections of major art museums, and the eighty-four-year-old artist had decided that he would not paint any more of the mural-sized paintings for which he was well known. However, the idea of creating a work to represent country music and its folk roots was intriguing to the Missouri-born painter, an amateur musician himself, who grew up with country music. When visited by representatives from the museum, including Country Music Hall of Fame member, recording artist, and singing cowboy film star Tex Ritter, Benton enthusiastically accepted the challenge.

Benton modeled many of the figures on real musicians he met in his travels, and the train is based on the one driven by locomotive engineer Casey Jones, the subject of a popular song recounting a famous train wreck in which Jones died.

Benton worked on the painting steadily throughout 1974, and it lacked only a coat of varnish and a signature when, on January 19, 1975, he returned to the studio in the carriage house next to his Kansas City, Missouri, home. While giving the mural one last inspection before signing it, Benton collapsed after suffering a massive heart attack and died.

The painting and complete collection of studies, including a rare clay maquette (three-dimensional model), became part of the museum’s permanent collection. Today, Country Music Hall of Fame and Museum visitors are fortunate to have the opportunity to view and appreciate this American masterpiece.