DeFord

Bailey

-

Inducted2005

-

Born

December 14, 1899

-

Died

July 2, 1982

-

Birthplace

Smith County, Tennessee

An influential harmonica player in both country and blues music, DeFord Bailey was one of the Grand Ole Opry’s most popular early performers and country music’s first African American star.

Musical Heritage and Beginnings

Born into a farming family in rural Smith County, Tennessee, Bailey lost his mother soon after his birth, and his aunt Barbara and her husband, Clark Odum, became his foster parents. Polio, which struck Bailey at age three, stunted his growth and left his back somewhat bent, but what he lacked in physical stature he made up for in talent and determination. As he later explained to researcher David Morton, he began learning harmonica as a young child: “My folks didn’t give me no rattler, they gave me a harp.”

The grandson of a fiddler, Bailey grew up in a musical family that played what he called “Black hillbilly music,” a tradition of secular stringband music that drew upon the same core repertoire shared by rural Black and white musicians alike. He also learned songs in church and developed a keen ear for the music he heard around him: the chugging of trains, the baying of hounds chasing foxes, and the sounds of animals on the succession of farms Clark Odum managed in Davidson and Williamson counties.

Bailey moved to Nashville in 1918 and spent the next six years working odd jobs, including stints as a houseboy, drugstore errand boy, and elevator operator. Meanwhile, he learned jazz, blues, and pop songs from recordings and from live shows he attended in local theaters. In doing so, he became a bridge between the rural folk music of his youth and the modern world of commercial popular music.

Songs

00:00 / 00:00

00:00 / 00:00

00:00 / 00:00

“The Harmonica Wizard” on Radio, Records, and Stage

A trip to Dad’s Auto Parts to buy parts for his bicycle led to Bailey meeting store owner Fred “Pop” Exum, who was fascinated by Bailey’s harmonica playing and began featuring him on radio station WDAD once Exum launched the enterprise in mid-September 1925. Here, Bailey met harmonica player and stringband leader Dr. Humphrey Bate, a country doctor from Castalian Springs, Tennessee, who began performing over Nashville’s powerful WSM not long after its October 5, 1925, debut.

Within months, Bate persuaded Bailey to come with him one night to appear on the show then called the WSM Barn Dance and then convinced station manager George D. Hay to let Bailey perform without an audition. By June 1926, Bailey was making regular appearances, and Hay soon dubbed him “The Harmonica Wizard.” Bailey was a dazzling performer, whose renditions of “Fox Chase,” “Pan American Blues,” and other tunes became harmonica classics. For the next fifteen years, Bailey remained one of the program’s best loved—and highest paid—stars.

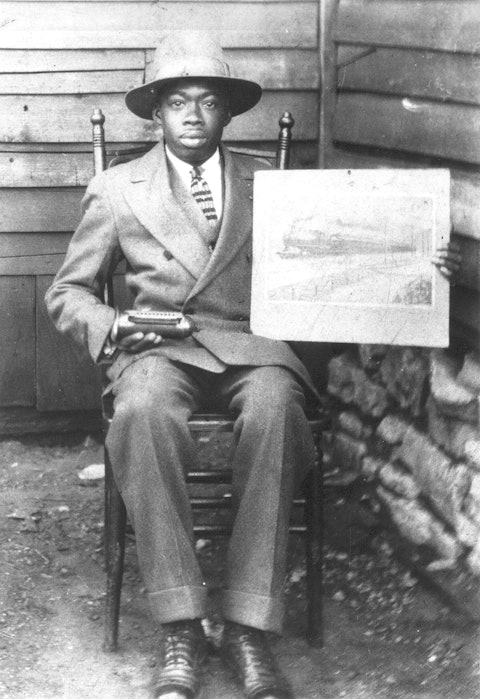

One evening in 1927, Hay spontaneously renamed the “WSM Barn Dance” while introducing several down-home performers immediately after a classical music program broadcast. Countering the view that “there is no place in the classics for realism,” Hay declared, the upcoming program “will present nothing but realism. It will be down to earth for the ‘earthy.’” As if to illustrate his point, Hay introduced Bailey, whose train-imitation piece “Pan American Blues” recreated the sounds of the L&N Railroad express train he remembered from his boyhood. In his introduction, Hay explained, “For the past hour, we have been listening to music largely from Grand Opera, but from now on, we will present ‘The Grand Ole Opry.’” Thus, Bailey helped inspire the familiar name of America’s longest-running radio show.

In 1932, WSM’s power jumped to 50,000 watts, giving Bailey an audience stretching from the East Coast to the Rocky Mountains, and scores of amateur and professional harmonica players—Black and white alike—eagerly tuned into his performances. Players also studied the records Bailey made for Brunswick and Victor Records, the latter recorded in 1928 at the first major recording session ever held in Nashville.

Personal appearances with Uncle Dave Macon, Roy Acuff, Bill Monroe, and other Opry members across the South and Midwest further extended Bailey’s influence. On the road, the expert showman sometimes picked guitar (in his left-handed, upside-down style), did yo-yo tricks, and embellished his harmonica tunes by beating rhythm with sticks or bones. Although usually well-received by white audiences, Bailey nevertheless faced the routine hardships and indignities of Jim Crow segregation while touring. Finding hotels and restaurants that would accept his patronage, for instance, often proved difficult.

Videos

“Fox Chase”

National Life Grand Ole Opry, 1965

On the road, DeFord Bailey sometimes picked guitar, did yo-yo tricks, and embellished his harmonica tunes by beating rhythm with sticks or bones. Although usually well-received by white audiences, he nevertheless faced the routine hardships and indignities of Jim Crow segregation while touring.

Photos

-

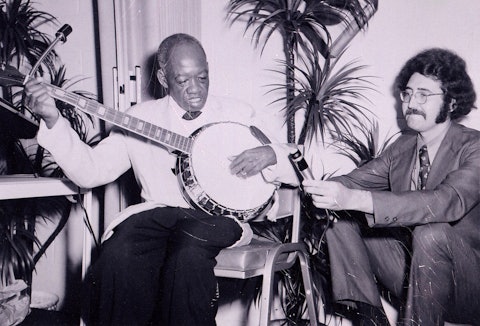

DeFord Bailey (left) and biographer David Morton, c. 1970s. Photo by Rayburn Ray, who worked for the Metropolitan Development and Housing Agency in Nashville.

-

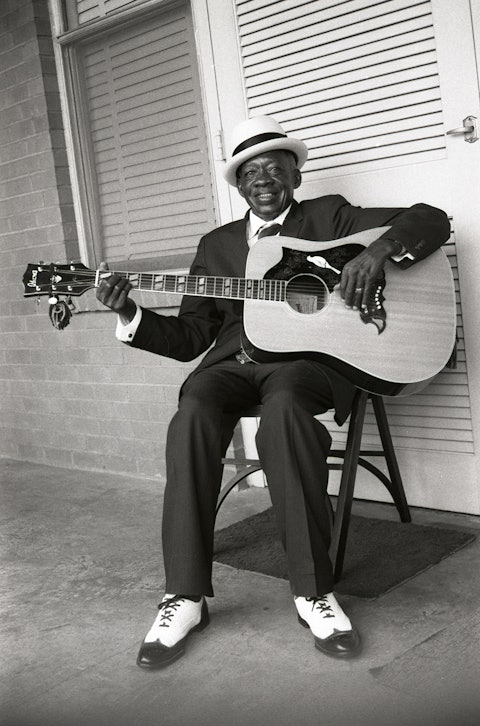

DeFord Bailey during a visit to the Country Music Hall of Fame and Museum, then located on Music Row, 1981.

-

DeFord Bailey playing guitar on the balcony of his Nashville apartment, c. late 1970s. Courtesy of David C. Morton.

-

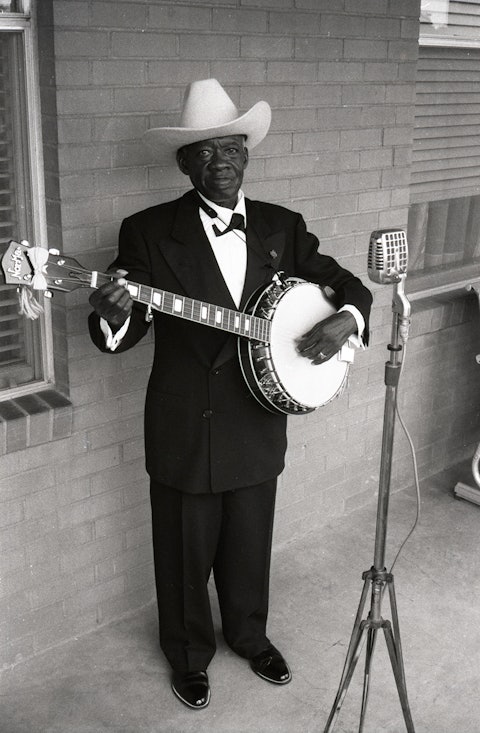

DeFord Bailey playing banjo on the balcony of his Nashville apartment, c. late 1970s. Courtesy of David C. Morton.

-

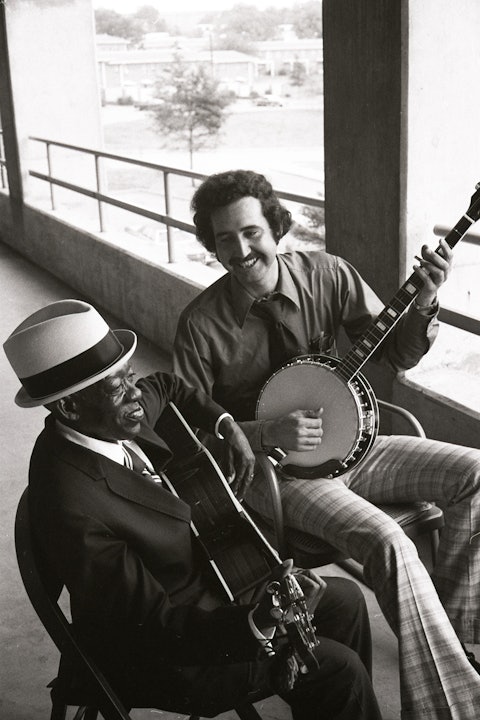

DeFord Bailey (left) and biographer David C. Morton playing music together, c. late 1970s. Courtesy of David C. Morton.

-

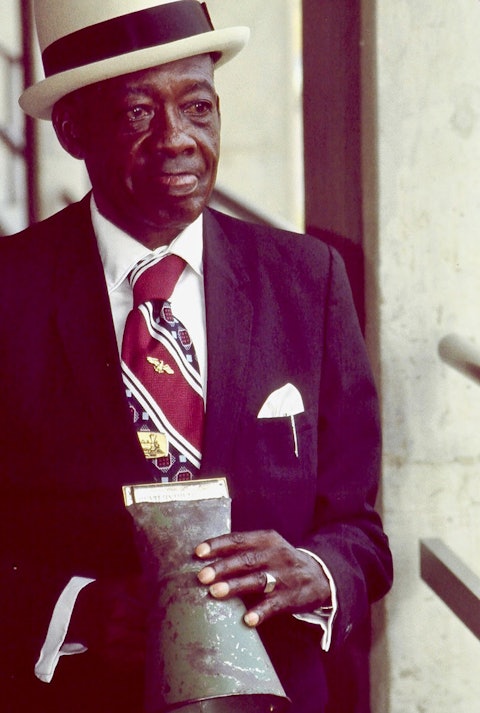

DeFord Bailey with a harmonica and a megaphone, c. 1980. Courtesy of David C. Morton.

-

DeFord Bailey with a harmonica, c. 1980. Courtesy of David C. Morton.

-

DeFord Bailey with his foot on a Coca-Cola bottle crate, c. 1930s. Courtesy of David C. Morton.

-

DeFord Bailey holding a harmonica and a photograph of the Pan American Express, c. 1920s. Courtesy of David C. Morton.

Opry Firing and Later Life

Bailey’s radio career came to a halt in 1941 amidst a dispute between the radio industry and the American Society of Composers, Authors, and Publishers (ASCAP) over licensing fees that organization charged radio stations for broadcasting its members’ songs. With no contract in place for most of that year, radio could not broadcast ASCAP-licensed songs without incurring heavy fines, and WSM warned Bailey against playing his ASCAP numbers, several of which were listener favorites. Station and performer remained at loggerheads, though, and, although he remained popular, WSM finally fired Bailey late that year.

Understandably angry and hurt, Bailey retired from professional music and made his living operating a shoeshine parlor and renting rooms in his home. He never stopped playing music, though, and rare guest performances on the Opry gave listeners occasional glimpses of his former heyday. Through it all, Bailey refused to become embittered, and stressed the importance of keeping “a good heart.” Whether onstage or off, his life was, as one scholar has noted, “a parable of integrity and survival.”

DeFord Bailey: A Black Star in Early Country Music, an informative biography written by David Morton with Charles Wolfe, was published by the University of Tennessee Press in 1991.

—Charles K. Wolfe and David C. Morton

Adapted from the Country Music Hall of Fame® and Museum’s Encyclopedia of Country Music, published by Oxford University Press