Jimmie

Rodgers

-

Inducted1961

-

Born

September 8, 1897

-

Died

May 26, 1933

-

Birthplace

Meridian, Mississippi

Musical Significance and Early Career

Jimmie Rodgers, known professionally as the “Singing Brakeman” and “America’s Blue Yodeler,” was in the first class of inductees honored by the Country Music Hall of Fame and is widely known as “The Father of Country Music.” From many diverse elements—the traditional folk music of his southern upbringing, early jazz, stage-show yodeling, the work chants of Black railroad section crews and, most importantly, African American blues—he forged a lasting musical style that made him immensely popular during his own lifetime and a major influence on generations of country artists to come. Gene Autry, Johnny Cash, Lefty Frizzell, Merle Haggard, Bill Monroe, Dolly Parton, Hank Snow, Ernest Tubb, and Tanya Tucker are only some of the dozens of stars who have acknowledged Rodgers’s impact on their music.

James Charles Rodgers was the son of a railroad section foreman but was attracted to show business. At age thirteen he won an amateur talent contest and ran away with a traveling medicine show. Stranded far from home, he was retrieved by his father and put to work on the railroad. For a dozen years or so, from World War I and into the early 1920s, he rambled far and wide on railroads, working as call boy, flagman, baggage master, and brakeman, all the while polishing his musical skills and looking for a chance to earn his living as an entertainer.

After developing tuberculosis in 1924, Rodgers gave up railroading and began to devote full attention to his music, playing on street corners, organizing amateur bands, touring with ragtag tent shows, taking any opportunity he could find to perform. Success eluded him until the summer of 1927.

In Asheville, North Carolina, Rodgers wrangled a regular (but unpaid) spot on local radio station WWNC and persuaded the Tenneva Ramblers, a stringband from Bristol, Tennessee-Virginia, to join him as the Jimmie Rodgers Entertainers. When the radio program was abruptly canceled, they found work at a resort in the Blue Ridge Mountains. There they learned that Ralph Peer, an A&R man for the Victor Talking Machine Company, was making field recordings in Bristol, not far away. Rodgers quickly loaded up the band, went to Bristol, and succeeded in gaining an audition with Peer. Before they could record, however, the group quarreled over billing and broke up. Deserted by the band, Rodgers persuaded Peer to let him record alone, accompanied only by his own guitar.

Songs

00:00 / 00:00

00:00 / 00:00

00:00 / 00:00

Meteoric Rise to Stardom

Encouraged by the public’s unusually strong response to Rodgers’s first release (“Sleep, Baby, Sleep,” paired with “The Soldier’s Sweetheart”), Peer arranged for Rodgers to record again in November at Victor’s home studios in Camden, New Jersey. From this session came the immortal “Blue Yodel (T for Texas),” Rodgers’s first big hit. Within months he was on his way to national stardom, playing first-run theaters, broadcasting regularly from Washington, D.C., and signing a contract for vaudeville tour of major southern cities on the prestigious Loew’s circuit.

In the ensuing five years, Rodgers traveled to Victor’s studios in numerous cities across the nation, including New York and Hollywood, eventually recording 110 titles, including such classics as “Waiting for a Train,” “Daddy and Home,” “In the Jailhouse Now,” “Frankie and Johnny,” “My Old Pal,” “T. B. Blues,” “My Blue Eyed Jane,” “Miss the Mississippi and You,” and the series of twelve sequels to “Blue Yodel” for which he was most famous. In 1929, Rodgers appeared in The Singing Brakeman, a fifteen-minute movie-short filmed in Camden by Columbia Pictures Corporation.

Best known for his solo appearances on stage and record, Rodgers also worked with many other established performers of the time, touring in 1931 with Will Rogers (who jokingly referred to him as “my distant son”) and recording with such country music greats as the Bill Boyd, the Carter Family, and Clayton McMichen, and, in at least one instance, with the legendary jazz trumpeter Louis Armstrong, who appears with him on “Blue Yodel Number 9 (Standin’ on the Corner).” One of the first white country stars to work with Black musicians, Rodgers also recorded with the fine St. Louis bluesman Clifford Gibson and the popular Louisville musical group the Dixieland Jug Blowers.

Videos

“Waiting for a Train”

The Singing Brakeman, 1929

Jimmie Rodgers brought to the emerging genre of “hillbilly music” a distinctive, colorful personality and a rousing vocal style that, in effect, created and defined the role of the singing star in country music.

Photos

-

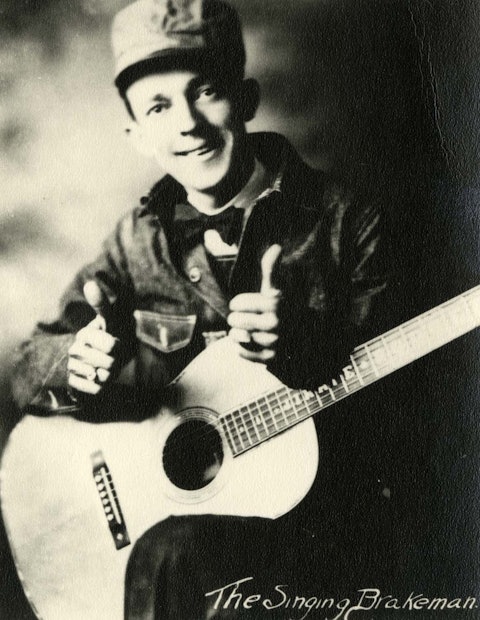

Publicity photo of Jimmie Rodgers, “The Singing Brakeman,” c. 1929.

-

Studio portrait of Jimmie Rodgers, holding his Weymann guitar, 1929.

-

Jimmie Rodgers (far left) with the Carter Family, in Louisville, Kentucky, 1931.

-

Jimmie Rodgers (left) and Will Rogers, in front of Rodgers’s home, Blue Yodeler’s Paradise, in Kerrville, Texas, 1931.

-

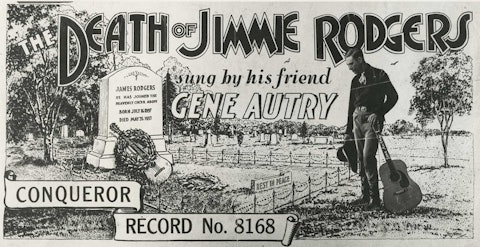

Advertisement for Gene Autry’s record “The Death of Jimmie Rodgers,” 1933.

-

Jimmie Rodgers in suit and bowtie, c. 1928.

-

Jimmie Rodgers playing his new, custom-made Weymann guitar, c. 1928

-

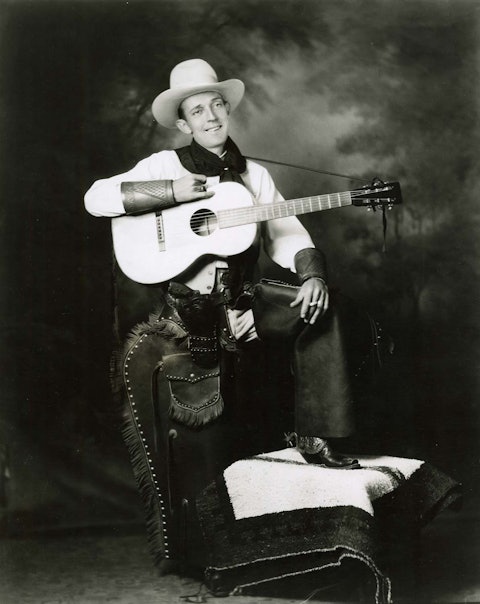

Jimmie Rodgers in a cowboy outfit, 1929.

-

Early professional photo of Jimmie Rodgers posing with guitar, c. 1921.

-

Jimmie Rodgers (far left) and his wife and daughter, visiting with Ralph S. Peer and his wife (couple seated in center), on the patio of Rodgers’s home, Blue Yodeler’s Paradise, in Kerrville, Texas, 1930.

Death and Enduring Legacy

Rodgers’s career reached its peak during the years 1928 to 1932. By late 1932, the Depression was taking its toll on record sales and theater attendance, and Rodgers’s failing health made it impossible for him to pursue the movie projects and international tours he had planned. Through the spring of 1933 he tried, with little success, to book personal appearances. In May, he went to New York to fulfill his contract with RCA Victor for twelve more recordings. It took him a week to finish the sessions, resting between takes. Two days later, on May 26, he collapsed on the street and died a few hours later of a massive hemorrhage in his room at the Hotel Taft.

Rodgers’s impact on country music can scarcely be exaggerated. At a time when emerging “hillbilly music” consisted largely of old-time instrumentals and lugubrious vocalists who sounded much alike, Rodgers brought to the genre a distinctive, colorful personality and a rousing vocal style that, in effect, created and defined the role of the singing star in country music. His records turned the public’s attention away from rustic fiddles and mournful disaster songs to popularize the free-swinging, born-to-lose blues tradition of cheatin’ hearts and faded love, whiskey rivers and stoic endurance.

Although Rodgers constantly scrabbled for material throughout his career, his recorded repertoire was remarkably broad and diverse, ranging from love songs and risqué ditties to whimsical blues tunes and even gospel hymns. There were songs about railroaders and cowboys, cops and robbers, Daddy and Mother, and home—plaintive ballads with all the nostalgic flavor of traditional music but invigorated by a distinctly original approach and punctuated by Rodgers’s yodel and unorthodox runs, which became his trademarks.

—Nolan Porterfield

Adapted from the Country Music Hall of Fame® and Museum’s Encyclopedia of Country Music, published by Oxford University Press