Eddy

Arnold

-

Inducted1966

-

Born

May 15, 1918

-

Died

May 8, 2008

-

Birthplace

Henderson, Tennessee

Eddy Arnold personified country music’s adaptation to the modern, urban world, and its transition from folk-based sounds, styles, and images to pop-influenced ones.

Early Life in Tennessee

Richard Edward Arnold came from a large farming family in Chester County, Tennessee, an upbringing that influenced his stage name, the “Tennessee Plowboy.” He took an interest in music early on. Arnold’s cousin lent him a Sears, Roebuck Silvertone guitar, which he learned to play with help from his mother and an itinerant musician, and he listened to records by Gene Autry, Bing Crosby, and Jimmie Rodgers on a wind-up Victrola.

Arnold would often slip away to some private spot to sing. He also sang at school near Jackson, Tennessee, and in church. “I discovered I could speak to people through songs in a way I never could by just talking,” Arnold later reflected.

Arnold’s father died when Eddy was eleven, and creditors auctioned the family farm the next fall. Thus, the Arnolds became sharecroppers during the Great Depression. Arnold sang at candy pulls, socials, and barbecues for $1 a night to help supplement his family’s income, while providing some relief from daily toil. In these circumstances, he jumped at the chance to pursue music professionally.

Beginning at age seventeen, Arnold worked on radio and in beer joints in Jackson, Tennessee, while also serving as an undertaker’s driver. Next, he moved to radio work in Memphis and St. Louis, singing and performing rube comedy as well.

Songs

00:00 / 00:00

00:00 / 00:00

00:00 / 00:00

From the Golden West Cowboys to Solo Stardom

Arnold’s prospects brightened when he joined Pee Wee King’s Golden West Cowboys as a featured singer in 1940. With King, he worked the Grand Ole Opry and the famous 1941-1942 Camel Caravan tour of military bases in the United States and Central America.

With his popularity rising, Arnold struck out on his own in 1943, broadcasting on WSM daytime shows and eventually the Opry. WSM station manager Harry Stone worked with Chicago publisher Fred Forster to bring Arnold to the attention of RCA Victor Records, and the singer recorded his first session for the label in WSM’s studios in December 1944. Meanwhile, he began to play shows at churches and schools.

Arnold’s early releases sold well, and he dominated the Billboard country chart for the remainder of the decade with hits such as “That’s How Much I Love You” (1946), “I’ll Hold You in My Heart (Till I Can Hold You in My Arms)” (1947), “Anytime” (1948), and “Bouquet of Roses” (1948). Many of his hits crossed over into the pop market, paving the way for later crossover acts, such as Jim Reeves and Patsy Cline.

With help from his then-manager, Tom Parker, Arnold became host of both the Mutual Network’s Purina-sponsored segment of the Grand Ole Opry and Checkerboard Jamboree, a noontime show shared with Ernest Tubb and broadcast from a Nashville theater. Recorded radio shows widened Arnold’s exposure, as did the CBS series Hometown Reunion, undertaken with the Duke of Paducah after Arnold left the Opry in 1948.

In 1949 and 1950, Arnold appeared in the Columbia films Feudin’ Rhythm and Hoedown, respectively. His earnings from recordings and road shows—together with a lucrative song scouting arrangement with music publisher Hill and Range Songs—enabled him to diversify his investments and build a fine home in Brentwood, Tennessee. He was determined never to be poor again, and he succeeded.

One of the first country artists to work the Las Vegas scene, Arnold was also a pioneering country television performer. He appeared on The Milton Berle Show in 1949 and hosted summer replacement series in 1952 and 1953 for Perry Como and Dinah Shore, respectively. Eddy Arnold Time, a series made in Chicago, debuted in 1955, and The Eddy Arnold Show, shot in Springfield, Missouri, followed in 1956.

Videos

“I’ll Hold You in My Heart”

Country Style, U.S.A., 1957

“This Is the Thanks I Get”

Eddy Arnold Time, 1954

“I discovered I could speak to people through songs in a way I never could by just talking.” — Eddy Arnold

Photos

-

Eddy Arnold on The Tonight Show Starring Johnny Carson, 1966.

-

Eddy Arnold publicity photo, 1950s.

-

Eddy Arnold signs autographs for fans, 1948.

-

Eddy Arnold with his daughter JoAnn, 1950.

-

Eddy Arnold with an unidentified disc jockey at WBT in Charlotte, North Carolina, 1950s. Photo by Elmer Warren.

-

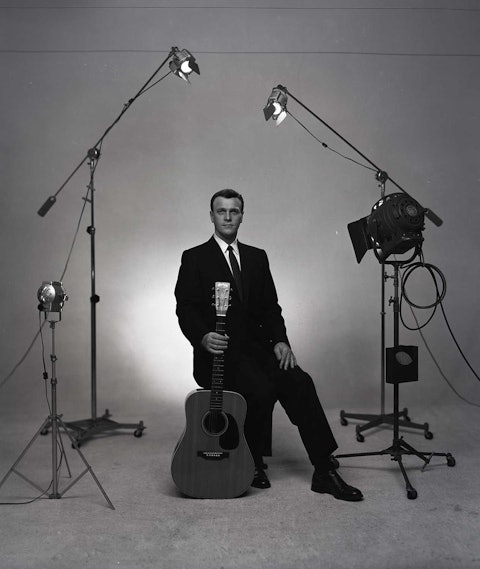

Eddy Arnold, 1957. Photo by Walden S. Fabry Studios.

-

From left: Eddy Arnold, Minnie Pearl, and Carl Smith. Photo by Walden S. Fabry Studios.

-

Eddy Arnold. Photo by Walden S. Fabry Studios.

-

Eddy Arnold, 1956. Photo by Walden S. Fabry Studios.

-

Eddy Arnold during a recording session at RCA Studio B.

Moving Uptown

During country music’s late-1950s slump, Arnold’s record sales fell off, as did his personal appearances, and he considered retiring from music. He experienced a new wave of popularity, however, when he traded his Tennessee Plowboy image for an uptown, sophisticated one.

By the mid-1950s, Arnold’s somewhat plaintive singing style had already begun to mellow, and songs such as “I Really Don’t Want to Know” (1954)—recorded with background harmony vocals and without the earlier trademark steel parts of Little Roy Wiggins—and a new version of “Cattle Call” (1955), recorded with an orchestra, anticipated the pop-oriented groove he would later establish with hits such as “What’s He Doing in My World” (1965), “Make the World Go Away” (1965), and numerous other #1 records, many of which crossed over to the pop charts.

In the mid-1960s, under the management of Gerard Purcell, Arnold began to wear tuxedos and make personal appearances with orchestras. His nightclub and TV work increased markedly, and his discs charted abroad as well, paving the way for international tours.

In 1966, Arnold was elected to the Country Music Hall of Fame. (Arnold and Johnny Cash, elected in 1980, were both forty-eight at the time of their inductions, making them the youngest inductees ever to receive the honor.) In 1967, he won the Country Music Association’s coveted Entertainer of the Year award, and in 1984, he received the Academy of Country Music’s Pioneer Award. In 1970, RCA honored Arnold with an award for reaching the sixty million mark in lifetime record sales, a number that reportedly topped eighty million by 1985. In 1993, RCA released the album Then and Now, marking Arnold’s fiftieth year with the label, an association interrupted only briefly from 1973 to 1975, when Arnold recorded with MGM.

Arnold continued to tour heavily during the seventies and beyond. He announced his retirement on May 16, 1999, during a concert at the Orleans Hotel in Las Vegas, but continued to record and released his 100th album, After All These Years, in 2005 on RCA. The National Academy of Recording Arts and Sciences inducted Arnold’s recording of “Make the World Go Away” into the Grammy Hall of Fame in 1999, and the Recording Academy gave him a Lifetime Achievement Award in 2005.

Arnold died May 8, 2008.

—John Rumble

Adapted from the Country Music Hall of Fame® and Museum’s Encyclopedia of Country Music, published by Oxford University Press