Wynonie Harris

Born in Omaha, Nebraska, in 1915, Wynonie Harris epitomized the emergence of star singers backed by R&B combos immediately after World War II. He attended Creighton University as a pre-med student but quit to become a dancer and comedian in local clubs. Early in the 1940s, he relocated to Los Angeles, where he became a featured vocalist for swing bandleader Lucky Millinder. Soon after, Harris began recording solo for several labels, with his greatest success coming on King Records, beginning in 1947. On King, his renditions of songs such as “Good Rockin’ Tonight” (1948) proved to be precursors of rock & roll. Elvis Presley not only covered “Good Rockin’ Tonight” in 1954 for Sun Records; according to King A&R man Henry Glover, “When you saw Elvis, you were seeing a mild version of Wynonie.” “Bloodshot Eyes,” Harris’s boisterous cover of Hank Penny’s 1950 country hit, made it to #6 on the R&B charts in 1951.

Wynonie Harris

Wynonie Harris

Harris left the King label in 1955 and afterwards recorded only sporadically, issuing a single on Atco in 1956 and another on Roulette in 1960. For a time, he owned a restaurant in Brooklyn before moving to Los Angeles, where he died of cancer in 1969.

The Orioles

The Orioles rank among the most important R&B vocal harmony groups of the late 1940s and early 1950s. The group, along with the Ravens and similar bird-named acts, pioneered in blending blues and gospel elements into their smooth sound. The Orioles were organized around lead singer Earlington “Sonny Til” Tilghman (1926–1981), who returned from military service to his native Baltimore about 1946 and won an amateur talent contest in a local club. Along with guitarist Tommy Gaither, baritone George Nelson, tenor Alexander Sharp, and bass Johnny Reed, Tilghman sang on street corners and in local bars, where the men were discovered by songwriter Deborah Chessler. Chessler rehearsed the group and secured them a spot on Arthur Godfrey’s Talent Scouts radio show in 1948.

The Orioles

The Orioles

Through this connection, the Orioles met Jerry Blaine of Natural Records (later renamed Jubilee), and eleven R&B chart records followed between 1948 and 1953, years when the group was also in great demand in city theaters. In 1953, the Orioles had a #1 hit with their hushed, inspirational rendition of “Crying in the Chapel,” a cover of a #4 country record by Darrell Glenn, the son of the song’s composer, Artie Glenn. (Country star Rex Allen’s version also went to #4 on that year’s country charts, while Elvis Presley scored a #3 pop hit with the song in 1965.

Big Al Downing

As a boy growing up in Lenapah, Oklahoma, Al Downing (1940–2005) enjoyed listening to Ernest Tubb, Hank Williams, and Porter Wagoner on the Grand Ole Opry and recordings of Fats Domino and other New Orleans R&B artists broadcast on Nashville’s WLAC.

Downing began playing piano on an abandoned instrument missing several keys. He eventually attracted the attention of white bandleader Bobby Poe, with whom he formed the Poe Kats. Their frenetic “Down on the Farm” (1958), originally released on the tiny White Rock label, has since become a rockabilly cult favorite. That same year, rockabilly star Wanda Jackson hired the Poe Kats, and Downing played on several of her recordings, including her well-known “Let’s Have a Party.”

Big Al Downing

Big Al Downing

After rock- and disco-styled releases with his own band during the 1960s and 1970s, Downing broke into the country music field with the 1978 Warner Bros. release “Mr. Jones.” All in all, he had fourteen country chart hits over the next ten years, among them the 1979 Top Twenty number “Touch Me (I’ll Be Your Fool Once More).”

Ivory Joe Hunter

Ivory Joe Hunter (1911–1974) was an exponent of what blues scholar Paul Oliver has called the West Coast blues fusion—a blend of country, boogie-woogie, jazz, and pop ballad styles that coalesced in the 1940s. “I was born in Kirbyville, Texas,” recalled Hunter, “and my father played bluegrass guitar on square dances and breakdowns. We had an old piano, but my mother was very religious, and the only thing she’d allow us to play on it other than religious songs was Jimmie Rodgers and Gene Austin. So I grew up playing and yodeling like Jimmie Rodgers.” Hunter left school after the eighth grade and began pursuing music professionally by age sixteen. He formed a band in Beaumont, Texas, where he had his own radio show on KFDM.

Ivory Joe Hunter

Ivory Joe Hunter

Ivory Joe Hunter

In 1942, Hunter began working in California clubs. Over the next eight years, he toured the West Coast and recorded for several labels. His hits for King Records included “Jealous Heart” (#2 R&B, 1949), written and recorded earlier by country singer Jenny Lou Carson. Although he placed many records on the R&B charts, including such classics as “I Almost Lost My Mind” and “Since I Met You Baby,” his diverse repertoire embraced spirituals, pop ballads, and country numbers like “City Lights,” a #1 hit for Ray Price penned by country singer-songwriter Bill Anderson. In 1973, Hunter did an album for Paramount titled I’ve Always Been Country and also appeared on the Grand Ole Opry. “He’ll Never Love You,” also featured on this set, dates from a 1972 Opry performance on which veteran announcer Grant Turner can also be heard. Shortly before his death, Hunter was honored by country stars George Jones, Tammy Wynette, and Sonny James, together with soul star Isaac Hayes, at a benefit performance in Nashville.

Ivory Joe Hunter, “He’ll Never Love You,” That Good Ole Nashville Music, circa mid-1970s

Ray Charles

As much as any twentieth-century musician, Ray Charles synthesized America’s great traditions of blues, jazz, gospel, country, and pop. The facts of his early career are well known: his birth as Ray Charles Robinson in 1930 in Albany, Georgia; the loss of his sight to glaucoma as a child; his musical education at what was then the St. Augustine (Florida) School for the Deaf and Blind; and his early work in small combos, including an otherwise all-white hillbilly group. Beginning with “I Got a Woman,” his 1954 breakthrough blend of gospel and blues recorded for Atlantic Records, Charles became one of the most influential performers in American music. Even as he was enjoying hits, he branched out with jazz albums and an early foray into country with Grand Ole Opry star Hank Snow’s “I’m Movin’ On.” Critics who thought Charles was merely dabbling hadn’t read the liner notes to his 1959 Atlantic album What’d I Say, in which he remarked, “Before anybody criticizes any kind of music, they ought to listen to it more. For example, I think a lot of the hillbilly music is wonderful. When I was a kid in Greenville, Florida, I used to play piano in a hillbilly band. I liked it. I think I could do a good job with the right hillbilly song today.”

Ray Charles

Ray Charles

Ray Charles with his band

Switching to ABC-Paramount in 1960, Charles kept pursuing an eclectic musical approach, recording classic pop (“Georgia on My Mind”), R&B (“Hit the Road Jack”), and two albums of country standards: Modern Sounds in Country and Western Music, Volumes 1 & 2. Among the tracks on the first album was the lushly arranged #1 single included in this set, “I Can’t Stop Loving You” (1962), written and earlier recorded by Country Music Hall of Fame member Don Gibson. Following those enormously popular albums, Charles scored a #4 pop hit with “Busted” (1963), penned by ace country songwriter Harlan Howard, also a Hall of Famer.

After signing with Columbia Records in 1982, Charles recorded several other country-flavored albums and chart-making duets with George Jones, Hank Williams Jr., and Willie Nelson. Charles was inducted into the Rock & Rock Hall of Fame in 1986 and received a Grammy Lifetime Achievement Award in 1987. Charles, who died in 2004, at age seventy-three, was posthumously elected into the Country Music Hall of Fame in 2021.

Ray Charles, “I Can’t Stop Loving You,” The Dick Cavett Show, 1973

Bobby Hebb

Most people may not realize that Bobby Hebb, perhaps best known as the writer and singer of the 1966 pop hit “Sunny,” had earlier been a longtime performer on the Grand Ole Opry. Hebb (1938–2010), a Nashville native, grew up near what is now Music Row. Both of his parents were musicians and encouraged him in his attraction to music of all kinds—classical jazz, blues, and country. As a boy, he learned to tap dance and play the spoons and, by the mid-1940s, was regularly working clubs, fraternity houses, and parties.

Bobby Hebb

Bobby Hebb

Bobby Hebb (center), playing spoons with Roy Acuff's Smoky Mountain Boys band.

Opry star Roy Acuff spotted Hebb on Owen Bradley’s WSM-TV variety show and hired him for his band. Hebb played with Acuff for about five years through the early 1950s. Years later, in 1960, Hebb acknowledged that association when he recorded “Night Train to Memphis,” a song popularized by Acuff in a 1942 recording. After “Sunny” hit in 1966, Hebb’s follow-up single was a soul interpretation of “A Satisfied Mind,” a #1 country hit for Porter Wagoner and a Top Five country hit for both Red Foley and Jean Shepard, all in 1955.

Solomon Burke

Known as “The King of Rock & Soul” for his R&B and pop hits of the early 1960s, Solomon Burke has been aptly described by music journalist Peter Guralnick as “an improbable mix of sincerity, dramatic artifice, bubbling good humor, and multi-textured vocal artistry.” Born in Philadelphia, Burke (1940–2010) was preaching on radio by age seven and traveling with a gospel tent show at twelve years old. While still a teenager, he attracted the attention of a local DJ, who steered him to the New York-based independent label Apollo in 1955.

Solomon Burke

Solomon Burke

In 1960, Burke switched to Atlantic, then a major R&B and soul label. Billboard writer Paul Ackerman, who advised Atlantic’s Jerry Wexler to sign Burke, also alerted Wexler to “Just Out of Reach,” a sentimental number earlier recorded by country singers Faron Young and Patsy Cline. The song became a Top Ten R&B hit for Burke in 1961, crossing over to the pop Top Forty as well.

Along with smooth pop ballads and rough soul songs, Burke recorded several more country standards, including the folksong “Down in the Valley,” the Eddy Arnold hit “I Really Don’t Want to Know,” and the Jim Reeves standard “He’ll Have to Go.” Burke’s multi-market voice was such that some members of his country audiences didn’t realize he was Black, and he was once even booked accidentally, he claimed, for a Ku Klux Klan rally.

Fats Domino

New Orleans singer, songwriter, and pianist Fats Domino, who was christened Antoine Domino Jr., enjoyed tremendous success as an R&B and pop star of the 1950s and early 1960s, while playing a leading role in rock & roll’s emergence. Domino (1928–2017) quit school at age fourteen to play clubs at night while working in a factory by day. Eventually, he was discovered by bandleader Dave Bartholomew, then scouting and producing for Los Angeles-based Imperial Records. From their first session came “The Fat Man,” a #2 R&B hit in 1950. Other R&B hits followed, and in 1955, Domino scored his first chart-making pop crossover success with “Ain’t It a Shame,” which he co-wrote with Bartholomew.

Fats Domino

Fats Domino

Fats Domino

Domino’s combination of personal charm, vocal warmth, and distinctive piano style proved a winning combination on many other hits, including “I’m in Love Again,” “I’m Walking,” “Blueberry Hill,” and remakes of the 1952 Hank Williams country hits “Jambalaya (On the Bayou)” and “You Win Again.” Of Domino, Bartholomew noted, “We all thought of him as a country-western singer. Not real downhearted, but he always had that flavor.”

Esther Phillips

The versatile Esther Phillips recorded everything from blues, R&B, and country to soul, jazz, and disco during her thirty-five-year career. Born Esther May Jones in Galveston, Texas, Phillips (1935–1984) grew up in both Houston and Los Angeles. At thirteen, she entered a talent contest in Los Angeles, where she was spotted by bandleader Johnny Otis. Otis produced her first records for the Modern and Savoy labels, and also took her on the road as a vocalist, billing her as Little Esther. She soon succumbed to the temptations of alcohol and drugs, however, and left show business for much of the 1950s.

Phillips got a fresh start with Lenox Records, on which she scored the #1 R&B and #8 pop hit “Release Me” in 1962. Recorded in Nashville, her rendition equaled—if not surpassed—in power and excitement those by country stars Ray Price and Kitty Wells (both 1954). Phillips followed with an entire Lenox album of country standards. Titled Release Me, it was later reissued by Atlantic as The Country Side of Esther Phillips. From the 1960s to the 1980s, Phillips made numerous appearances at jazz festivals, recorded for Atlantic and other labels, and enjoyed an R&B and pop hit in 1975 with “What a Diff’rence a Day Makes.”

Joe Hinton

Evansville, Indiana, native Joe Hinton (1929–1968) began his musical career in gospel music as a member of the Blair Singers and the Spirit of Memphis Quartet. In 1953, Don Robey, president of Peacock Records (for whom the latter group recorded), convinced Hinton to shift from the sacred field to secular music, and, in response, Hinton signed with Back Beat, a related label for which he recorded until his death. Hinton failed to make an impact on the R&B charts until 1963, with “You Know It Ain’t Right.” The following year, he scored the biggest hit of his career with his rendition of Willie Nelson’s “Funny How Time Slips Away,” notable for Hinton’s electrifying high falsetto ending.

Joe Hinton

Joe Hinton

Arthur Alexander

Although initially marketed as an R&B and pop act, Arthur Alexander possessed such a plaintive voice that some listeners who heard his self-penned 1962 Dot Records hits, “You Better Move On” and “Anna (Go to Him),” thought he was a country artist who had crossed over into pop. Also country-flavored was his interpretation of the 1963 Bobby Bare country hit “Detroit City,” written by country singer-songwriters Danny Dill and Mel Tillis, the latter a Country Music Hall of Fame member.

Arthur Alexander

Arthur Alexander

Arthur Alexander

Alexander’s country music leanings came naturally. Born in 1940 in Florence, Alabama, he grew up listening to both white and Black music. “I loved Roy Rogers, man, I loved Gene Autry, Rex Allen,” he recalled. “Every Saturday I was in the movies watching them guys.” After singing gospel and R&B as a teenager, he recorded for the Judd label in 1961. The next year, his “You Better Move On” became the first major hit to emerge from the close-knit group of musicians led by producer Rick Hall in Muscle Shoals, Alabama. Shortly thereafter, Alexander moved to Nashville, where he did most of his recording through the remainder of the decade. Though the Beatles, the Rolling Stones, and other bands covered his original songs, personal problems and indifferent treatment by the music industry led to Alexander leaving show business in the mid-1970s. After a nearly twenty-year hiatus, he triumphantly returned to the spotlight with his 1993 album, Lonely Just Like Me, recorded in Nashville for Elektra Records. What might have been a sustained comeback, however, was cut short by Alexander’s death later that year.

The Supremes

With a slew of #1 hits including “Where Did Our Love Go,” “Baby Love,” and “I Hear a Symphony,” the Supremes reigned as one of the most successful acts in all of popular music during the 1960s. Recording for Detroit’s mighty Motown label, the vocal trio projected a sound and visual style that conveyed both youthful innocence and urban sophistication. With Diana Ross’s sweetly enticing vocals usually front and center, the Supremes represented what many considered the epitome of the Motown Sound.

The most famous version of the group consisted of Ross (born 1944), Florence Ballard (1943–1976), and Mary Wilson (1944–2021). They signed with Motown as teenagers in 1961 but did not score their first hit until 1964, with “Where Did Our Love Go.” The following year, they released five albums, including The Supremes Sing Country, Western & Pop. That album included their poignantly understated version of “It Makes No Difference Now,” written by Country Music Hall of Fame member Floyd Tillman and popularized by Cliff Bruner’s Texas Wanderers in 1938. On this version, each of the Supremes sings a verse, and it shines here as a rediscovered gem of the glory years of this fabled singing group.

The Staple Singers

Many fans regard the Staple Singers as “The First Family of Gospel,” but founder Roebuck “Pops” Staples (1914–2000) actually began his career as a blues guitarist in his hometown of Winona, Mississippi. Around 1947, he bought his first electric guitar and formed the Staple Singers with his children Cleotha (1934–2013), Pervis (1935–2021), and Mavis (born 1939), later adding Yvonne (1937–2018) to replace her brother, who had been drafted by the army. In the mid-1950s, the Staples began recording, first for United Records and later Vee-Jay.

The Staple Singers

By the early 1960s, the Staple Singers had joined other entertainers in the growing civil rights movement then being led by Reverend Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., whose message of interracial Christian brotherhood appealed to religious and musical traditions shared by Blacks and whites alike. Thus, the Staples’ 1966 Epic recording of “Will the Circle Be Unbroken,” a song first popularized by the Carter Family in the 1930s and widely performed by country singers ever since, reflected the temper of the times. The track was recorded in Nashville and produced by Billy Sherrill, later famous for his work with Tammy Wynette and George Jones, among others.

By 1968, the Staple Singers had shifted to Memphis-based Stax Records, where they cultivated a more commercial and contemporary “soul folk” sound featuring Mavis’s superb lead contralto. Early in the 1970s, they scored pop hits like “Respect Yourself” and “I’ll Take You There.” By mid-decade, the act had moved to the Curtom label, where they enjoyed a #1 pop hit in 1975 with “Let’s Do It Again.”

While she continued to work with the Staples into the 1990s, Mavis pursued a parallel solo career, based mostly on secular recordings. Pops made his first solo LP in 1987 and later filled acting roles in film and onstage. He, too, continued to record and tour as a solo artist. The Staples joined country singer Marty Stuart to record “The Weight” for MCA’s 1994 all-star release Rhythm, Country and Blues. The death of Pops Staples, followed by those of other members, ended the decades-long career of the Staple Singers, though Mavis has continued to record and tour.

Joe Tex

“We sort of combined the blues with country and came across with a pop sound,” said Joe Tex in 1972, looking back at seven years of soul hits. Born Joseph Arrington Jr. in Rogers, Texas, Tex (1935–1982) won a Houston talent contest in high school. The prize was a trip to New York, where he won several amateur shows at the famous Apollo Theater. There, singer Arthur Prysock saw him and ultimately steered him to King Records, for whom Tex recorded some modest-selling sides.

Joe Tex (left) with Buddy Killen

Joe Tex (left) with Buddy Killen

In the early 1960s, after recording for the Ace and Anna labels, Tex met Nashville music publisher-producer Buddy Killen, who signed him to Dial Records. Early Tex releases on that label, recorded in Nashville, were unsuccessful, however. Finally, a Muscle Shoals, Alabama, session yielded “Hold What You’ve Got,” which in 1965 peaked at #2 on the R&B charts and at #5 on the pop charts. Subsequent recordings included “Half a Mind,” earlier a hit for Grand Ole Opry star Ernest Tubb and written by country singer-songwriter Roger Miller. In his performance, Tex scat sings like Miller and alludes to Miller’s first big crossover hit, “Dang Me.”

Early in the 1970s, Tex became a Muslim preacher, calling himself Yusuf Hazzlez, but returned to music for one more hit, “Ain’t Gonna Bump No More (With No Big Fat Woman),” in 1977.

Etta James

“I want to show that gospel, country, blues, rhythm & blues, jazz, and rock & roll are all just really one thing,” Etta James once explained. “Those are the American music, and that is the American culture.” Over a career that spanned more than fifty years, the versatile James illustrated her point with a wide array of recorded music. Born Jamesetta Hawkins, James (1938–2012) grew up with her grandparents in Los Angeles, where she sang in church. After moving to San Francisco, she was drawn to R&B and was discovered by bandleader Johnny Otis, who arranged her recording of “Roll with Me Henry” (issued under the title “The Wallflower” on Modern), a #1 R&B hit in 1955.

Etta James

Etta James

James signed with Chess in 1960. Over the next sixteen years, she had numerous releases on the company’s Chess, Argo, and Cadet labels, including classic R&B performances such as “Something’s Got a Hold on Me” and “Tell Mama.” Among her late 1960s Cadet releases was “Almost Persuaded,” on which she applied her raw-edged, emotive voice to the 1966 David Houston country hit, written by Billy Sherrill and Glenn Sutton. After her departure from Chess, James went on to record well-regarded albums for several labels and also performed at blues and jazz festivals and clubs worldwide.

Joe Simon

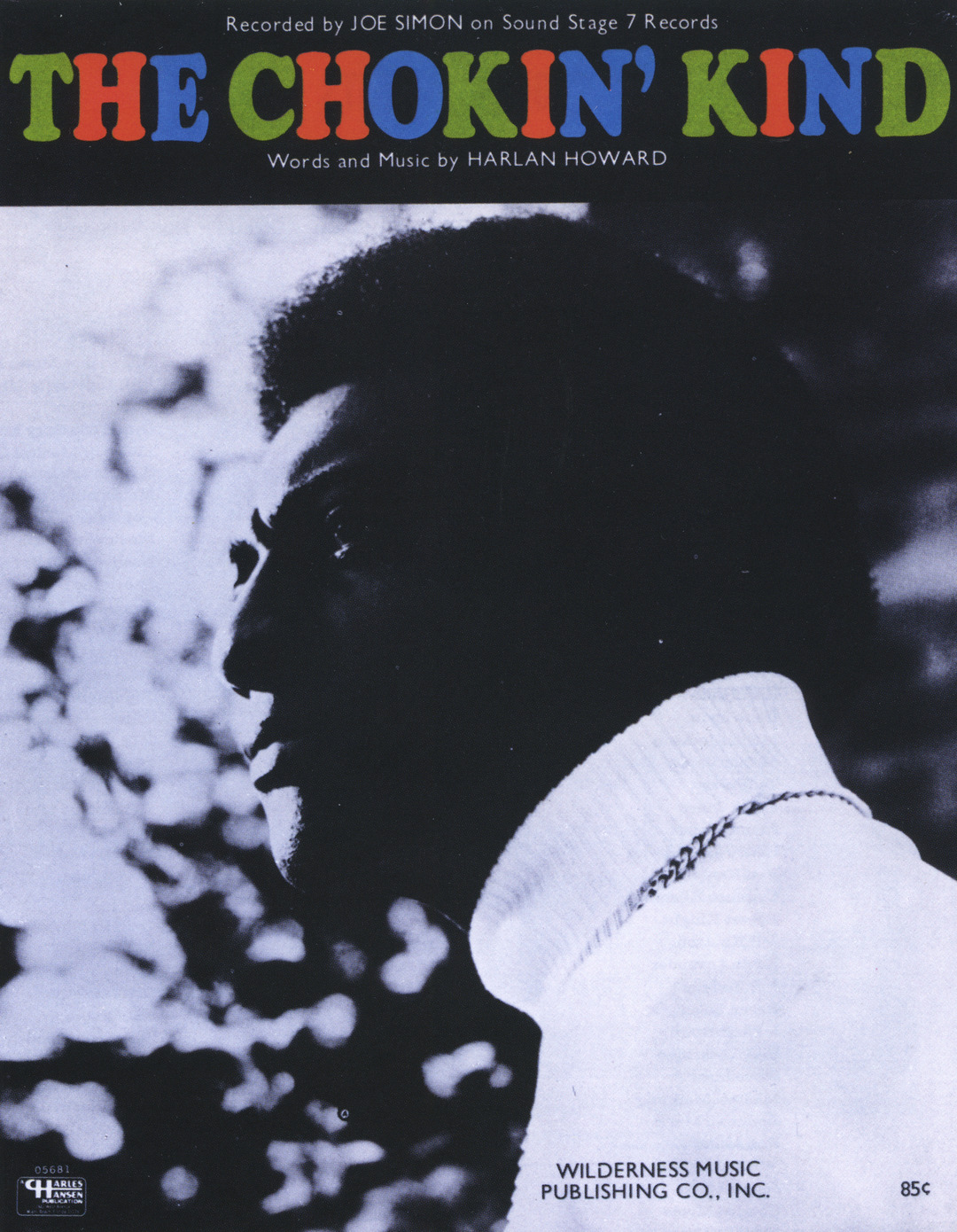

Soul star Joe Simon (1936–2021), a native of Simmesport, Louisiana, began his career with the Golden West Gospel Singers in Richmond, California, where he moved in the late 1950s. He and other members of the group formed a doo-wop act named the Golden Tones, which recorded for the small Hush label. Next came solo recordings for Hush, Irrall, and Vee-Jay. After Vee-Jay, Simon signed with the Sound Stage 7 label, for which Nashville R&B disc jockey John Richbourg (“John R.”) served as producer. Simon scored several soul hits, followed in 1969 by his #1 R&B and #12 pop hit, “The Chokin’ Kind,” for which he won a 1969 Grammy for Best Rhythm & Blues Vocal Performance, Male. A 1967 country hit for Waylon Jennings, the song was written by country tunesmith Harlan Howard, who had also pitched it unsuccessfully to Ray Charles.

Joe Simon

Joe Simon

In 1970, Simon moved to Spring Records. Among the records he made for the label was the 1973 album Simon Country, which included his rendition of such well-known country tunes as “Five Hundred Miles” and “You Don’t Know Me.” In 1980, Simon signed with Posse Records and made an album in Nashville produced by Grand Ole Opry star Porter Wagoner.

Dorothy Moore

Even as disco and funk were eclipsing southern soul during the late 1970s, Jackson, Mississippi, native Dorothy Moore (born 1946) bravely carried soul music’s banner. Moore began her career at Jackson State University, where she led an all-female group called the Poppies. The ensemble recorded for Epic Records and scored a minor pop hit with “Lullaby of Love” in 1966. Going solo, Moore worked as a session singer for a time, then signed with Mississippi-based Malaco Records and earned two chart hits in 1976. The first was “Misty Blue” (#2 R&B, #3 pop), initially a 1960s country and pop hit for both Wilma Burgess and Eddy Arnold, and a 1976 country hit for Billie Jo Spears. The second was Willie Nelson’s “Funny How Time Slips Away” (#7 R&B), her favorite song.

Dorothy Moore

Dorothy Moore

Moore placed several more R&B discs on the charts but, during the early 1980s, dropped out of the recording scene. She returned in 1986 with a gospel album, Giving It Straight to You, recorded in Nashville for Word Records’ Rejoice label. In 1996, “Misty Blue” was featured in the soundtrack for the movie Phenomenon, starring John Travolta.

Dorothy Moore, “Misty Blue,” Nashville Now, 1984

Listen: Disc 2