Eddie

Bayers

-

Inducted2021

-

Born

January 28, 1949

-

Birthplace

Patuxent River, Maryland

After more than forty years as a first-call Nashville studio musician, Eddie Bayers was the first drummer to be inducted into the Country Music Hall of Fame. His journey to that point was at times been difficult, but his love of music and his determination to be involved in it carried him through.

A Nomadic Youth

Born January 28, 1949, in Patuxent River, Maryland, Edward Howard Bayers Jr. had a nomadic childhood. His family moved often, following his fighter pilot father’s military assignments in Maryland, California, and then North Africa for four years. (The decorated war veteran served in both the Korean War and World War II, earning the Navy Cross for his role in the Battle of Midway in 1942.) When the elder Bayers retired, the family settled in Nashville, northeast of his mother’s hometown of Summertown, Tennessee.

Despite their frequent moves, the family always had a piano in their home, and Bayers remembers feeling “something innate” drawing him to the instrument as a child. He began learning to play melodies from memory, then started formal, classical training under the tutelage of a Russian instructor, Professor Conus, while the family lived in North Africa. Bayers also played accordion as a child, but he did not pick up the drums until high school.

Bayers’s parents split up when he was fourteen. His father, Bayers says, experienced culture shock when reentering civilian life, “and he basically left the family and started another family.” Two years later, at sixteen, Bayers was effectively orphaned when his mother and sister Vicky died in a car accident. Knowing his father’s new family wouldn’t take him in, Bayers followed a high school friend and bandmate to Philadelphia and began playing organ in a local band with a summertime residency on the Jersey Shore. When that band broke up, however, Bayers again found himself unmoored: he slept on the boardwalk, panhandled, and entered eating contests to get food (these performances earned him the nickname “Eddie Cakes”).

Bayers kept his piano skills sharp during this time, thanks to a benevolent club owner who let him practice and play during the day. That’s how his future bandmate, Joey Joya, first encountered Bayers and, impressed by Bayers’s playing, asked him to join Joya’s band, the Big Bear Revue. Bayers remained in the band for several years playing keyboards and drums, until receiving an invitation to join an R&B group that played frequently at a Las Vegas casino. He nearly didn’t make it, however. A member of the Big Bear Revue came from a Mafia-affiliated family and thought Bayers knew too much about his family’s illegal activities to leave New Jersey. Bayers had to beg for permission to go during a harrowing late-night meeting.

Songs

00:00 / 00:00

00:00 / 00:00

00:00 / 00:00

All told, Eddie Bayers has played on around 300 gold and platinum albums.

Shifting from Keyboards to Drums

While in Las Vegas, Bayers reconnected with Brent Maher, whom he knew from Nashville and who was working at Las Vegas’s United Recording Studios under renowned sound engineer Bill Porter. Bayers and Maher would later work together in Nashville, but not until after Bayers moved yet again, this time to Oakland, California, becoming a member of the Edwin Hawkins Singers gospel group. While in the Bay Area, Bayers also fell in with a bunch of musicians that included Jerry Garcia of the Grateful Dead and Tom Fogerty and Doug Clifford of Creedence Clearwater Revival, and through them got some studio work.

Bayers moved back to Nashville in 1974, again living out of his car, this time at a rest stop, while establishing himself in the city. Two early decisions would prove key. First, Bayers auditioned to play piano at the Carousel Club in Printer’s Alley. Top session drummer Larrie Londin hired him on the spot for his group. Londin mentored Bayers in his transition to drumming, and the two remained good friends up until Londin’s death in 1992. Meanwhile, at Audio Media Recorders—a studio owned by friends of his—Bayers worked for free but met several people who would be key figures in his career: guitarist and producer Paul Worley became Bayers’s partner in the Money Pit recording studio from 1984 until 2004, while producer Jim Ed Norman was among the first to hire Bayers for country recording sessions.

Bayers’s standing in Nashville grew as he played percussion on George Jones’s My Very Special Guests, Dolly Parton’s 9 to 5 and Odd Jobs, Ricky Skaggs’s Highways & Heartaches, and other albums. In the early 1980s, his friend Brent Maher—now a producer—recruited Bayers to play drums on recordings for an up-and-coming duo called the Judds. Bayers subsequently played on all the Country Music Hall of Fame duo’s albums. His resume eventually expanded to include work with pop, rock, and soul artists, including John Denver, Elton John, Mark Knopfler, Aaron Neville, Bob Seger, and Steve Winwood. All told, Bayers has played on around 300 gold and platinum albums.

Videos

“Workin’ Man Blues” with Musician of the Year nominees, Lee Roy Parnell, and Marty Stuart

Country Music Association Awards, 1993

“Movin’ Out” with Mike Snider

Country Music Hall of Fame & Museum Musicians Spotlight, 2017

-

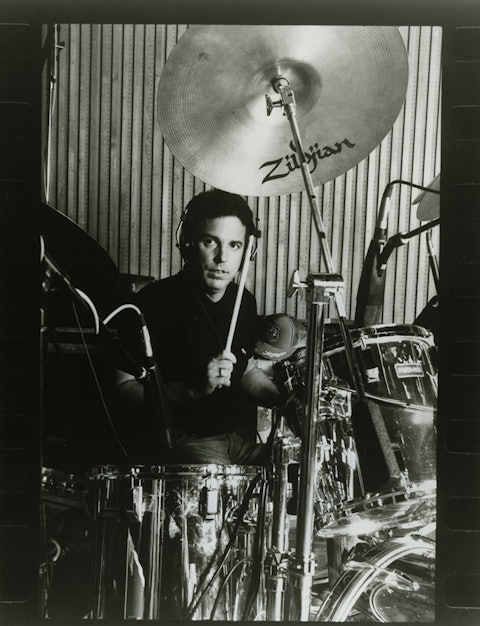

Eddie Bayers publicity photo.

Starting Over

Bayers’s career could have ended in 1985, when he broke his wrist and sustained a serious hand injury in a motorcycle accident. His injuries necessitated eight months off work, and he played on a few albums, including Rosanne Cash’s King’s Record Shop, while still in a cast. Bayers had to relearn to play the drums and began using an open-handed style following the accident. He credits in particular producers Steve Buckingham and Brent Maher and recording artists Rodney Crowell and Vince Gill as key people who helped him return to work.

In 2002, Bayers formed an all-star band, the Players, with studio musicians Paul Franklin, John Hobbs, Brent Mason, and Michael Rhodes. They intended to perform together only once, during a concert featuring several big-name special guests, “but it stuck, and we became a band . . . a brotherhood,” Bayers later explained. The Players stayed together for eleven years, until Hobbs’s retirement.

Bayers has been a member of the Grand Ole Opry’s house band since 2003, when he turned a six-month fill-in assignment into a long-running job. From 1991 through 2010, Bayers was named the Academy of Country Music’s Drummer of the Year fourteen times, including eleven consecutive times from 1991 through 2001.

Above all, Bayers believes his job is always to serve the singer and the record, and that sensitivity has served him well. “I want the inspiration to come from the artists and their songs. I want to be their drummer,” he says. “I tell them, ‘I know some things about drums, but whatever ideas you have, I want to hear them. I’m not bringing the last successful effort I had in with me. This is your record; I want to be your drummer.’”

—Angela Stefano Zimmer